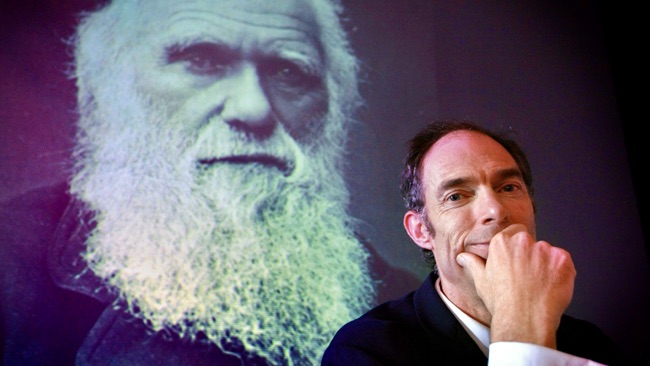

Charles Darwin and his great-great-grandson Chris Darwin, who is honouring his legacy (supplied).

By Julie Nance

The father of evolutionary theory, Charles Darwin, expressed remorse late in life about not doing more to help the earth’s creatures. A century and a half later in the lower Blue Mountains, his great-great-grandson Chris Darwin is devoting his life to addressing this regret. Julie Nance chatted to the environmentalist about his personal and global initiatives, from setting up nature reserves to launching an app designed to improve the health of the planet and its inhabitants.

When I learned that Charles Darwin’s great-great-grandson lives only three suburbs from my home, I was excited. I was intrigued how an Englishman, who ironically flunked biology at high school, ended up in Glenbrook and how he was honouring his great-great-grandfather’s legacy.

Chris Darwin’s philosophy in life is to “love ourselves, others and our planet”. He also believes there’s a “massive benefit in a lot of people doing small things”.

Inspired by his great-great grandfather’s achievements as a naturalist and his own personal values, Chris and his wife Jacqui founded the not-for-profit charity, The Darwin Challenge.

Key Points

- Small acts, like choosing one or more meat-free days a week, have big impacts.

- To restore the health of our planet and reduce the risk of future disasters, we need to reduce our ecological footprint. Chris Darwin is modelling how we can each do this.

- Chris has found that ‘loving yourself, loving others and loving the planet’ is a philosophy for contentment.

In 2017 the organisation launched the Darwin Challenge App which encourages the western world to adopt a moderate meat-eating diet. The app, endorsed by Sir Paul McCartney, has won many design and digital awards.

The Darwin Challenge app in use (copyright Chris Darwin).

By choosing one or more meat free days, the app shows how you are improving your health and your world: “Small acts, big impacts”. You can track your own meat free days and achievements but also see how others around the world are faring and the cumulative benefits.

I downloaded the app and it shows my one meat-free day logged so far has contributed to 1,511,576 meat-free days for everyone using the app.

It shows some fascinating metrics that highlight the combined benefits of everyone using the app so far including: 7 square kms of forest saved; 8.5 million kms of greenhouse gases avoided; almost 18 square kms of marine reserves created; and 56,000 people fed (moved out of chronic malnutrition). The Darwin Challenge website has explanations on each metric.

When you click on each statistic on the app there’s also an explanation of the figures, attributed to bodies such as the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organisation and Global Footprint Network. The app has a disclaimer: “We are more confident with some metrics than others. At the end of each metric, we give a confidence rating out of 10. As we develop the app and do more research, those confidence ratings will improve.”

Chris, aged 62, used to be a big meat eater and gradually reduced his intake after measuring his ecological footprint and “realising meat is one of the biggest problems to solve”. He says the “footprint factor is large with the livestock industry responsible for 74 per cent of deforestation”.

With generous fellow donors, an app design team led by Bulgarian Plamena Slavcheva, and a long list of other experts and creatives, the organisation is so driven to halt the increase in global meat consumption that many of the members work for free, including Chris. Profits are directed into “promoting the issues we feel passionately about”.

Chris explains: “The idea is to motivate people to do small things such as having a meat free day a week. We want to see peak meat and dairy by 2040. So, not only just stopping the increase but actually getting it to start coming down over the next 17 years. It’s an audacious goal but we are travelling in the right direction.”

Charles and Chris Darwin’s love of the Blue Mountains

Charles Darwin famously fell in love with the Blue Mountains in 1836. He was 26 years old and visiting Australia on his round-the-world voyage on the HMS Beagle. It was during this epic expedition that Darwin questioned creationism for the first time.

Charles Darwin as a young man (supplied).

You can follow in Charles’ footsteps on the Charles Darwin Walk at Wentworth Falls that is named in his honour.

I asked Chris if his famous ancestor’s interest in the Mountains and its species influenced his decision to move here.

He says: “Who knows, was Charles silently guiding us in life? My sister did her PhD on the Galapagos tomatoes. When I said ‘Sarah, that cannot be a coincidence’ she said it was. We are all guided by our ancestors in all sorts of subtle ways. I would love to think that I’m completely rational and unaffected by Charles Darwin the person, but I think there probably are all sorts of influences.”

Chris moved to Glenbrook 15 years ago with Jacqui and their three children, now aged 16, 18 and 20.

“I love the upper Mountains and my wife loves the city so my mother had the inspiring idea to live halfway between the two, which was such a clever concept,” he says.

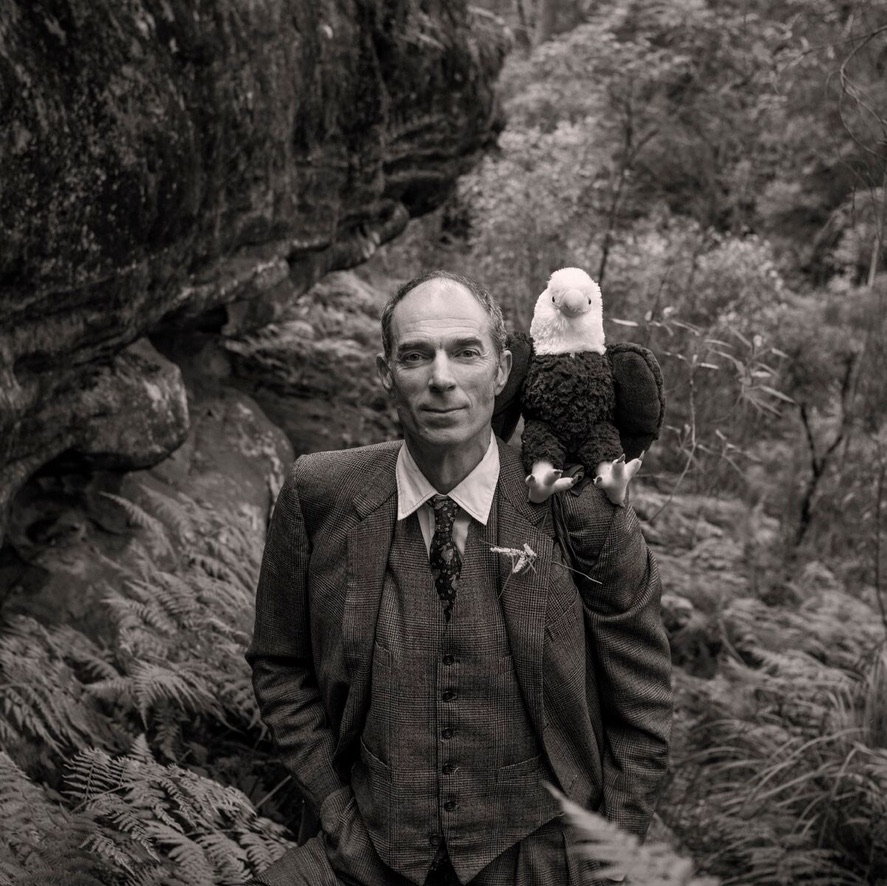

Chris in the Blue Mountains (Jim Rolan).

“If you can’t be first, be peculiar”

When we connected by phone, Chris had just emerged from six days in bed with the flu. His illness did nothing to diminish his characteristic energy and enthusiasm: “I’m excited about this phone call. I’m really interested. Can I hear a bit about you and your role?”

I enjoyed explaining what a community storyteller for the Planetary Health Initiative involves and how interested I was in documenting his journey.

Chris took me by surprise when he asked: “Do you have a life vision? I mean, do you know what success looks like for you? What would need to happen by what date for you to go okay, I’ve done my work?”

What answer could I possibly give a man who declared many years ago his “big, hairy audacious goal was to prevent the mass extinction of species”? How could I not feel like I was coming up short?

I knew the queries weren’t intended to judge or compare. I understood Chris wanted to quickly get to the essence of the person about to probe him with questions. He was genuinely interested in what I had to say.

It’s been a few years since Chris shared his life challenges and ambitions in short documentaries, newspaper articles and a TEDxSydney talk.

He enjoys quoting his grandmother’s advice after he failed a school exam: “Christopher, if you can’t be first, be peculiar.”

Chris took her comments to heart. After graduating from Oxford Polytechnic with a Bachelor of Science in Psychology and Geography (Honours), he worked in advertising in the UK. In the 1980s he started London’s first bicycle rickshaw taxi service and a year later was official photographer and assistant organiser for the first Round Britain Windsurf Expedition.

Chris has had plenty of firsts – photographed here with the bicycle rickshaw taxi service (Shuna Darwin).

Chris also organised the world’s highest dinner party on top of Peru’s highest mountain (Milton Sams).

A philosophy for contentment

After emigrating to Australia in 1986 at the age of 25, Chris continued his career in advertising but at the age of 30 was deeply depressed.

“I basically swallowed the promise that the way to gain happiness and contentment is to get lots of money, lots of possessions and lots of experiences, and then you will be happy,” he says.

“It definitely didn’t work for me and ended in a suicide attempt. I had to try and find an alternative philosophy for contentment. With the help of a lovely psychologist, I found one that does work which is ‘love yourself, love others and love the planet’ and you will find contentment. I’ve been doing those three things ever since and it works for me.”

Chris and friends at North Head in his Sydney advertising days. The high-flying lifestyle took its toll (supplied).

Turning away from living a six-planet lifestyle

Chris upended his life. He left advertising, sold his house, his car and most of his belongings and worked as a climbing guide for the Australian School of Mountaineering in Katoomba.

He thought he was living an “eco life in Blackheath – a vegetarian, without a car”. However, when he read the book Radical Simplicity by Jim Merkel, and measured his ecological footprint, he was shocked to discover he was “living a six-planet lifestyle”.

“This meant that if everybody lived like me, we’d need six planets to support humanity,” he says. “I thought, this is absolutely ridiculous, I’ve got to do something serious.”

Chris was fortunate to have an inheritance to draw on that came through the generations, most likely from the income Charles Darwin gained from publishing The Origin of Species in 1859 and other works.

Before his death in 1882, the naturalist wrote: “I feel no remorse from having committed any great sin, but have often and often regretted that I have not done more direct good to my fellow creatures.”

This moving quote from his great-great-grandfather inspired Chris to use his inheritance to address this remorse.

On being an Ambassador for Bush Heritage Australia

While volunteering for Bush Heritage Australia in 2003, Chris donated $300,000 to the conservation charity. A 68,600 hectare pastoral station in Western Australia was purchased with the funds, on traditional land of the Badimaya people. The area was named the Charles Darwin Reserve which Chris says is “biodiversity motivated” – protecting animals, plants and vegetation communities.

Chris and son Ras many years ago on the Charles Darwin Reserve (Annette Ruzicka – Bush Heritage Australia).

“Charles Darwin’s regret is something that encouraged me,” Chris says.

“I have been a fundraiser for Bush Heritage over the years and raised quite a lot of money for them to buy reserves around Australia. They are a top organisation and I’m proud to be an ambassador.”

Feeding his soul and reducing his ecological footprint

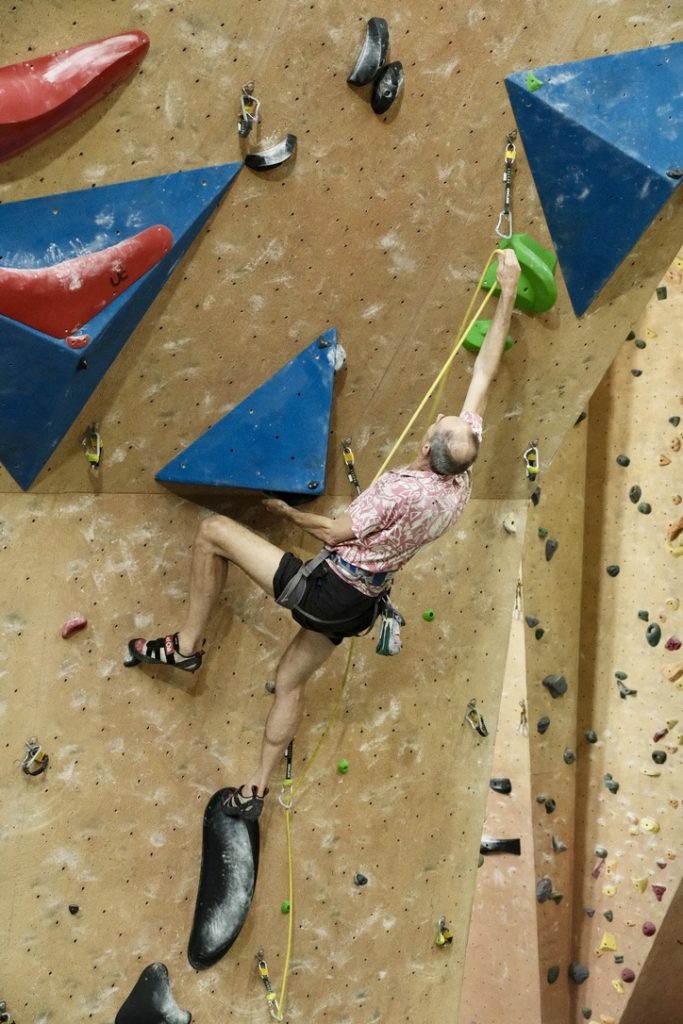

Thirty-two years after starting as a rock-climbing guide in the Blue Mountains – the latter 10 years working for High and Wild – Chris is still a part-time guide.

Chris in guide mode at the snow (Monty Darwin).

Chris clearly knows what feeds his soul. This includes venturing into the patch of rainforest near his home and feeding the Eastern Yellow Robins most mornings.

“I take down some worms from the compost or maggots or whatever else is in there, and the birds come and eat from my hand,” he says. “Isn’t that a great way to start the day?”

Chris feeding an Eastern Yellow Robin near his home (Muse Storytelling).

Over the past 15 years Chris has worked hard to reduce his individual footprint, from six planets down to 0.8 of a planet.

He hasn’t flown in eight years and believes he won’t go on a plane again due to the “massive footprint of a flight”. When visiting family in the UK prior to COVID, he travelled by container ship.

Chris has an electric car but tries to cycle as much as possible, including once to Melbourne for Christmas. Before he peddles off to the Blaxland shops, he checks if his neighbours need anything.

He elaborates: “I go on trains a lot more than I used to because the footprint has been found to be quite small. I am vegan. I don’t buy life consumables. I try where possible not to use fossil fuels which is hard to achieve. I try not to buy any new clothes. When my lovely friends are throwing out their clothes, they throw them in my direction.”

Chris measures everything he does. If he buys a battery, he adds it to his footprint spreadsheet. Part of his ‘loving myself’ philosophy means he doesn’t drink alcohol and avoids sugar.

Chris jokes: “My friends still talk to me. They think I’m a harmless, fairly weird individual. Doing all of this is the reverse of a sacrifice. It’s made my life. It’s given my life purpose.”

Teaching climbing also gives Chris’ life purpose, as does competing in the sport. In action at the NSW Masters Climbing Championships 2023 where he came fourth (Sydney Indoor Climbing Gym, Villawood).

Jacqui is a vegetarian and while she and their children support his endeavours, they lead their own paths without any pressure or expectation from Chris to emulate his behaviour.

“Winston Churchill had this lovely line: ‘Ignore what people say just look at what people do’,” Chris says.

“I don’t preach to people. I just do things and people might notice and be motivated to do one or two things positive to help the planet.”

A famous forebear

I was curious to find out if Chris ever gets sick of people asking him ‘what has been the impact of being related to Charles Darwin?’

Chris replies: “I don’t get sick of it because it’s a really important question.

“I’m sure your grandparents and your parents had an impact on you. I’m just incredibly lucky that Charles was such an interesting character and a clear thinker. He has offered me a lovely way of trying to understand the truth of the world around me.”

I ask: “So you’ve never really felt the pressure of him being a hard act to follow?”

Chris replies: “It does give you this sort of sense that you have got to do something big. I mean, here am I talking about peak meat and dairy by 2040. Where does that come from? We all like to think we’re all independently driven, but maybe it is that big, ambitious background that has played a part.”

I thank Chris for his generosity with his time and he ends the interview in the same warm way it began:

“Really nice to have a chat. Have a happy-filled life until our paths cross again.”

Chris’s personal philosophy that helped transform his life is the foundation for The Darwin Challenge: Loving ourselves, others and our planet (copyright Chris Darwin).

Loving others (copyright Chris Darwin)

Loving our planet (copyright Chris Darwin)

If you’re interested in learning more and exploring the app, visit The Charles Darwin website or access the links below:

Apple: download in the App store

Android: download in Google Play

If this story has raised any issues for you, you can access support from the following services:

Lifeline: 13 11 14 | Text 0477 13 11 14 | lifeline.org.au

Beyond Blue: 1300 224 636 | beyondblue.org.au/forums

This story has been produced as part of a Bioregional Collaboration for Planetary Health and is supported by the Disaster Risk Reduction Fund (DRRF). The DRRF is jointly funded by the Australian and New South Wales governments.