A ‘pale phase’ (pale grey, almost white) Greater Glider looking out of its hollow in May 2023. It was located in burnt forest on one of the study sites of Drs Judy and Peter Smith, at the southern end of Blue Mountains National Park (Peter Smith).

By Julie Nance

Extreme drought, heat waves and the 2019/2020 Black Summer bushfires had a devastating impact on Greater Glider populations in the Blue Mountains National Park. Studies by local ecologists, Drs Peter and Judy Smith, contributed to the native marsupial being listed as ‘endangered’. However, their latest research reveals in some areas the Greater Glider has recovered with “extraordinary” numbers. Peter and Judy share their exciting findings with Blue Mountains Planetary Health Initiative writer Julie Nance.

They are furry, silent, super cute and have been likened to a ‘gliding koala’. With a low nutrient diet of eucalypt leaves, the Greater Glider is usually lethargic but can launch itself off the top of a tree and glide for up to 100 metres.

It can manoeuvre dramatically as it goes through the air, twisting its shoulders to turn itself almost at right angles to dodge trees.

Up until the 1990s, the Greater Glider was found in roughly equal numbers in the lower and upper Blue Mountains.

They tend to favour tall, mature, moist forests on richer soils. A nocturnal animal, they need to feed every night and spend their days sheltering in hollows of large eucalypt trees, often in gullies.

Peter and Judy have been tracking the Greater Glider’s plight over many years since they created a partnership in 1985 as P & J Smith Ecological Consultants. Their fauna and flora surveys and studies have taken them throughout the Blue Mountains, the Sydney region and across NSW and Australia.

Drs Judy and Peter Smith in national park next to their Blaxland home where they have lived for almost 40 years and raised three children (Julie Nance).

A short drive from their Blaxland home, Judy and Peter would venture out at night with their spotlight and binoculars and find high numbers of Australia’s largest glider.

“Greater Gliders were scattered around the lower Mountains,” Judy says. “You could just whip down to Euroka Clearing at Glenbrook or Blue Gum Swamp Creek at Winmalee and spot them.”

The pair regularly took TAFE classes spotlighting in these areas, with the Greater Glider’s distinct eye shine easily detected along the bush tracks.

“People had no idea there were animals like this in the local bush, with the Greater Glider a favourite because it is so spectacularly beautiful,” Peter says. “Up to 2015 we were increasingly noticing they were harder to find. They just weren’t where they used to be.”

Judy adds: “You’d feel like a fraud telling TAFE students ‘we’re going off to see Greater Gliders’ and they wouldn’t be there.”

In 2015/16, with the support of a Landcare grant, Judy and Peter conducted research in the Blue Mountains Local Government Area (LGA) to evaluate the situation. Their studies revealed the Greater Glider was still “hanging on in good numbers” at higher elevations. Surveys of the animal further afield at Wombeyan and Jenolan also revealed healthy populations. This was part of wider arboreal (tree dwelling) mammal surveys for the Kanangra-Boyd to Wyangala Conservation Partnership.

Dark phase Greater Glider in Wiarborough Nature Reserve in December 2016, showing its long tail which can be up to 60cm (Peter Smith).

In the lower Blue Mountains, the situation was grim. Judy and Peter found there had been a marked decline in numbers, with historical records confirming this had occurred since the 1990s.

The ecologists evaluated various factors to explain the dramatic downturn, including temperature and rainfall. Predation was also evaluated but was ruled out.

“Powerful Owl numbers have been increasing in the Blue Mountains since the 1990s and they take a lot of Greater Gliders,” Peter says. “However, we found no evidence that the presence or absence of Greater Gliders depended on whether there were Powerful Owls at the site. The factor that had the greatest influence was temperature. Greater Gliders had disappeared from the sites where temperatures were highest.”

Peter says Greater Gliders are a heat sensitive animal, better adapted to the cold than to the heat.

“As the temperatures have increased across the Blue Mountains, they have disappeared from most parts of the lower Mountains,” he says.

Peter and Judy’s research findings contributed to the Greater Glider being listed federally in 2016 as ‘vulnerable’.

Extreme drought and heatwave conditions leading up to the Black Summer fires impacted Greater Glider numbers throughout the World Heritage Area.

The peak of the drought was 2019 – the hottest and driest year on record in Australia. Although there were plenty of eucalypt trees available, Greater Gliders need young, soft, moist foliage for their nutrition. With only dry leaves on offer, gliders died from dehydration and heat stress.

At this critical time for wildlife, Peter, Judy and daughter Kate Smith published their comprehensive book Native Fauna of the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area. They worked on the project from 2015 in their spare time, alongside their Greater Glider research.

The inside cover of the book explains: “The book celebrates the outstanding diversity of the native fauna of the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area. We describe the distribution, abundance, habitat and conservation significance of every mammal, bird, reptile and frog species that has been reliably recorded in the area since European settlement.”

The book, available in Blue Mountains bookshops, features Kate Smith’s illustrations throughout and has a small section on the Greater Glider (p. 39).

Not long after the book was published, the ferocious fires arrived.

“The Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area was one of the worst affected areas with about 80 per cent burnt,” Peter says.

Moist, higher elevation plateau forest and gullies that were traditionally spared from fire, were severely burnt in the Black Summer fires. This refuge for fauna was significantly diminished.

“We were really worried about how the Greater Gliders fared with so much of their habitat impacted,” Peter says.

In 2020 Peter and Judy went back to re-survey past sites, both in the Blue Mountains LGA and at Wombeyan and Jenolan.

They found the impact on the Greater Glider depended on fire severity.

The badly burnt areas fared the worst. All the eucalypt foliage had been killed in the fires, either by burning (crown fire) or scorching (very hot fire). There was no food for the Greater Gliders in the immediate aftermath of the fires.

“They disappeared,” Peter declares bluntly. “They were present in pre-fire surveys in 2019 but there were none at all afterwards.”

Severely burnt forest near Bell in March 2020, two months after the Black Summer bushfires (Peter Smith).

In other sites that had burned at low to moderate severity, live eucalypt foliage remained after the fires.

“We found there were still Greater Gliders present,” Judy says. “Their numbers were reduced, but they were still there, which was really encouraging considering they are so sensitive to fire. This was mainly in Wombeyan but also down the end of Megalong Valley in the Blue Mountains National Park.”

Moderately burnt forest in one of the study sites at the southern end of Blue Mountains National Park in November 2020 (Peter Smith).

Dark phase Greater Glider feeding on regrowth foliage in November 2020 in burnt forest on the same study site at the southern end of Blue Mountains National Park (Peter Smith).

In the unburnt areas, numbers had been reduced because of the preceding drought and heatwaves, but not as much as they had in the burnt areas.

Post-fire mapping showed that 84 per cent of the Greater Glider habitat located throughout the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area had been burnt. However, post-fire surveys found the resulting loss of population was not 84 per cent but 60 per cent.

“It was still a massive loss,” Peter says.

Peter and Judy conducted repeat surveys at the sites in 2020, 2021 and 2022. Their most recent survey in May this year produced a mixture of bad, good, and wonderful news.

Peter reveals the bad news first.

“Three and a half years after the fires, there was still no sign of Greater Gliders at sites that had been severely burnt,” he says.

“But at plots that had been less severely burnt, where there’d been some live foliage after the fire and Greater Guiders survived, they were still there, and their numbers were increasing.”

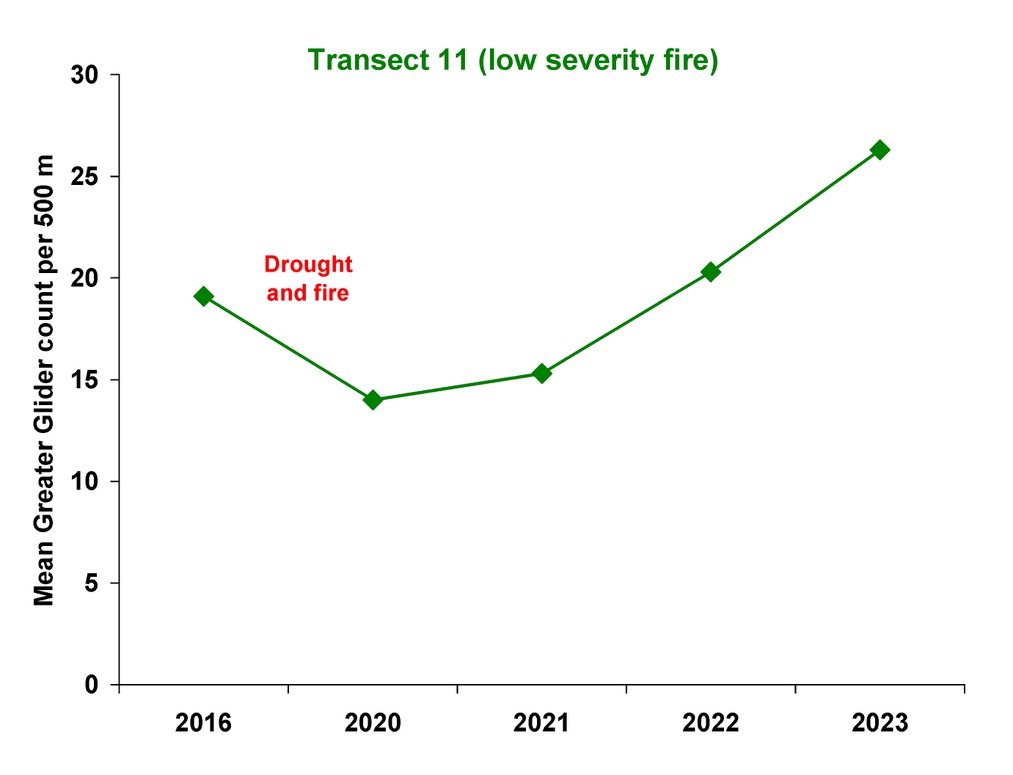

The Greater Glider has an annual breeding season. The first season after the fire in 2020 was in Peter’s words “a dud”, leading to no increase in the population. However, the population was building after the two subsequent breeding seasons in 2021 and 2022. Judy and Peter attribute this to the wet conditions and good plant growth since the fires.

A graph showing an example of the recovery of Greater Glider numbers at one of Judy and Peter’s study sites at the southern end of Blue Mountains National Park. This site was burnt only at low severity. The first post-fire survey revealed there had been a distinct reduction in Greater Glider numbers compared with 2016, due to extreme drought, heatwaves and fire.

Vegetation in the study site highlighted in the graph (southern end of Blue Mountains National Park) in May 2023. It’s a favourable habitat for Greater Gliders which has always supported good numbers. It now supports “exceptionally good numbers“. (Peter Smith).

Exciting discoveries

When Judy and Peter conduct their surveys, they mark out a 500-metre section of track during the day and come back at night with their binoculars and spotlight to count Greater Gliders and other arboreal mammals over a one-hour period. They repeat the count in the same location over three nights.

Judy preparing a study site. “We get measurements of the habitat – the type and health of the trees, their height and the hollows, so we have information to match against the animals. At night we go looking on each side of the centre line, or transect, for all arboreal mammals.” (Peter Smith)

Peter searching with his spotlight (Judy Smith).

The May 2023 surveys provided much needed, encouraging news for Peter and Judy.

“In some of the plots there were extraordinary numbers of Greater Gliders, actually higher than the pre-fire numbers we were getting,” Peter says.

Judy adds: “On one track in the southern Blue Mountains National Park, we recorded up to 30 Greater Gliders over an hour. That was like a Greater Glider every two minutes.”

Peter adds: “Greater Glider Pitt St. It was really exciting to see those sorts of numbers.”

Years of Greater Glider surveys by Peter and Judy have provided valuable information from which informed decisions can be made at a local, state and federal level.

Their tireless work has contributed to the Greater Glider moving in July 2022 from ‘vulnerable’ to ‘endangered’ on Australia’s list of threatened wildlife.

Although their study findings are encouraging, Peter says it has been in a limited geographical area where the high numbers have been recorded. He says because of a lack of recovery in severely burnt areas and other ongoing climate change impacts, there is unlikely to be a change in the endangered status for Greater Gliders.

“What our studies show is the big difference between really badly burnt areas and the lightly burnt areas,” he says. “If you can reduce fire severity, it’s going to have a big effect on the Greater Glider. They come back really well if the fires haven’t been too severe. If you can’t stop the fires, at least try to stop the really severe parts of fires.”

Peter says hazard reduction is an obvious, major tool but “you’ve got to think beyond that”.

“You’ve got to really concentrate the hazard reduction burning in fire break areas rather than trying to get the generalised, broad area hazard reduction,” he says. “We don’t have the windows of opportunity to do these, and the benefits are only short term.”

Outlook for Greater Gliders in the lower Mountains

Greater Gliders are now seven times more abundant at elevations above 500m than at elevations below 500m.

Peter says one of the few sites in the lower Mountains where Greater Gliders have been found in recent times is Blue Gum Swamp Creek, but not in the numbers they were previously.

Judy reflects: “In the 80s and 90s before obvious climate change, they were at Euroka Clearing in good numbers, at Fitzgerald Creek, and at the back of Blaxland tip in the Cripple Creek area.”

Peter and Judy nicknamed this pale phase Greater Glider ‘Snowy’ at Blue Gum Swamp Creek in February 2021 (Peter Smith).

The future for Greater Gliders in the lower Mountains doesn’t sound bright.

Peter laments: “It’s really the upper Mountains where you’ve got to concentrate your efforts. Climate change is probably just making the lower Mountains uninhabitable for Greater Gliders.”

It’s clear when chatting to Peter and Judy, they have a personal affection for wildlife and a particular soft spot for Greater Gliders.

Judy says: “I think Greater Gliders are quite smart. They watch us as much as we watch them. When you see the babies on the back of the mothers, just like a possum carries their young, you’ll pick up the big eyes’ shine, and then this tiny eye shine on the back.”

Peter concludes: “They are big, fluffy and cute and when you see them glide, they’re spectacular.”

A Greater Glider sketch by Kate Smith. In 2022 Kate released the children’s book ‘Drawing Australian Gliders’.

This story has been produced as part of a Bioregional Collaboration for Planetary Health and is supported by the Disaster Risk Reduction Fund (DRRF). The DRRF is jointly funded by the Australian and New South Wales governments.